After the Abundance conference in Washington last weekend, one of the most controversial takes was this post by Eli Dourado

It’s safe to say that wasn’t the end of the conversation to judge by the comments, the reposts, the counterblogs and the comments and reposts of those. Nothing makes better rage-bait than besmirching the railway.

But it’s a doorway into a much bigger question, which I’ve struggled with: what exactly does abundance want from transport? And why is it that the instinctive answer seems to be ‘shiny trains’?

An Abundance of Movement

In principle, abundance1 ought to be the most disruptive idea to come to transport in fifty years. There are two reasons for this.

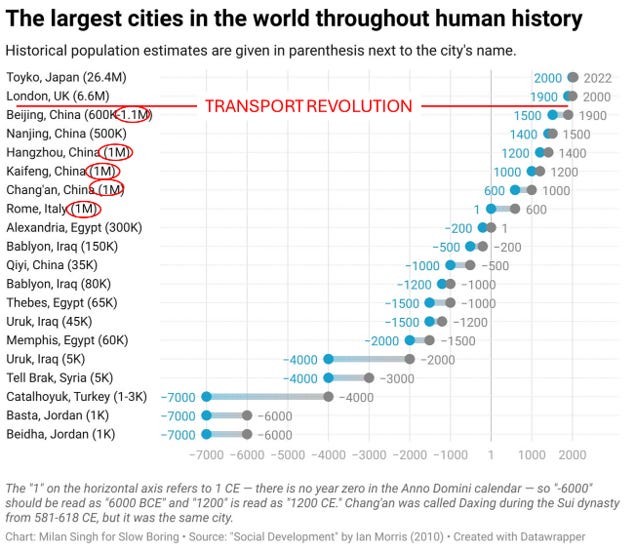

First, transport is one of the greatest examples of the power of abundance. Prior to 1800, every city in human history had been limited to a population of around a million people, and bound within a space defined by the distance of an hour’s walk. Roughly 200 years ago, new technologies began dissolving that limit: the omnibus, the railway; the tram; the automobile.

Not only did these technologies exist, but they were abundant – available to those on modest incomes and allowing them to live far from where they worked. They wove themselves into everyday life, letting citizens fill their larders from distant fields; letting factories source and sell over oceans; enabling everything from holidays to professional sports leagues. Throughout the modern era, cheap and plentiful travel has carried us out of privation and towards utopia.

The enemy at the traffic lights

But the second reason that abundance should be disrupting transport thinking is that for the past fifty years, most transport policymaking has been fighting against that trend towards more movement. Indeed transport policy is probably the one place in modern statecraft where degrowth – the bête noire of the abundance movement – is seen as respectable.

Since the 1960s, the runaway success of the car and the airplane has been seen as more of a blessing than a curse. Practical limitations of space and a growing environmental mission2 meant that the focus of transport shifted from getting into people into places towards keeping vehicles out, spreading around a fixed amount of capacity in ‘fairer’ ways, and reducing that capacity in the pursuit of other goals. In 1910, radical socialists3 talked about rebuilding roads to unleash their potential; in 2025 this is unimaginable for most policymakers.4

There are reasons for this shift that I will come back to shortly. For now, let’s observe that better-through-more abundance agenda is naturally a challenge to the way transport planners do things today.

Transport for Abundance

This framing would suggest some obvious ideas for trying to get more, better transport into play – several of which are in Eli’s tweet:

Electric vehicles, to drive cheaper, better and greener

Autonomy, to remove the drudgery of driving

New kinds of automated public transport and ride-hailing

Small personal vehicles like e-scooters, e-bikes, and conventional bikes, that provide enjoyable journeys and can bypass some of the legal limits on car travel

Deliveries on demand by airborne drone

Faster, more direct planes for quicker long-distance journeys

And more generally, it’s a really exciting time for transport innovation as powerful batteries, more effective motors, autonomous control and more mean we’re inventing new transport ideas faster than ever.

So why is it, then, that the go-to transport thought for many abundance people is ‘more trains’? Especially high-speed ones and metro/underground ones.

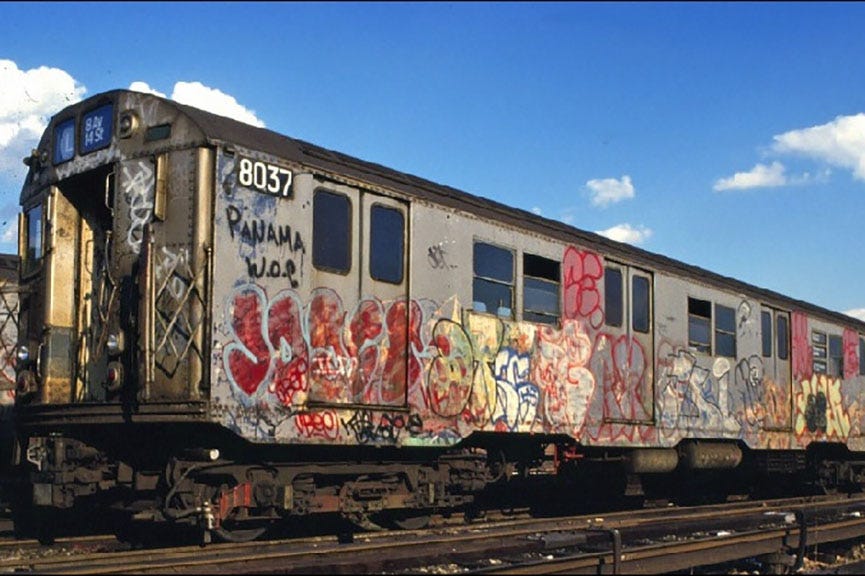

This seems counterintuitive. Once upon a time, trains were transformational – but that hinged on the steam train’s monopoly on powered transport, which is now ancient history.5 Trains carry a relatively small share of travel (about 10% here in the UK). The fact they’re trapped on their own network of tracks means they don’t scale. They’re expensive and have a habit of getting more expensive whenever you try to upgrade them. Eli is right to say it’s a curious priority to set.

But rather than dismiss this as unwise passion, isn’t it more productive to ask why people are so determined to push a seemingly counterintuitive answer?

Hex Appeal

Transport is seldom about how you travel – it’s far more about where you start and where you end, and why that journey was worth making in the first place. For the abundance movement, that’s overwhelmingly about cities.

The YIMBY movement is deep in the foundations of abundance, and within that is a belief that productive cities must be allowed to get taller and wider. That means that residents and new arrivals can find affordable homes; it also means that the most productive places on earth face no artificial barrier to their onward rise.

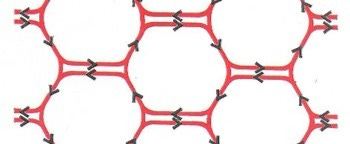

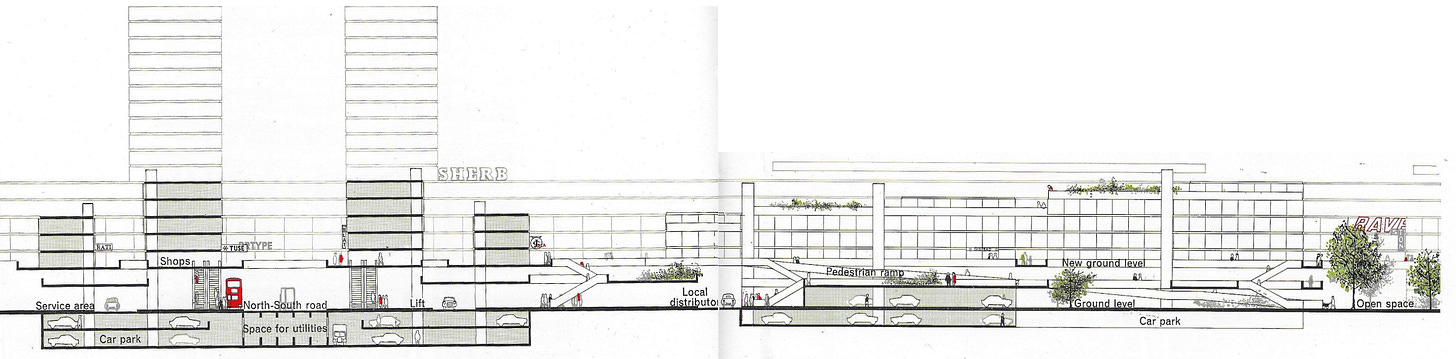

And it is in cities where many of the usual tools of transport, particularly the motor car, begin to fail. This isn’t sentiment – this is mathematics. In 1963, the UK government published a landmark report about what the rise of the motor car would mean for Britain’s built environment. One of their case studies, looking at what it would mean to accommodate the car in the central London neighbourhood of Fitzrovia, tried to work out for the first time what it would take to absorb the expected traffic.

With a purely car-driven solution, they expected peak car traffic to rise from around 3,000 vehicles/hour to 40,000. Six motorways, with five lanes in each direction, would be required just to get the people in and out of this one neighbourhood. In the words of the report,

“When we considered the consequences for the primary network of a vast continuous spread of areas similar to our study area, for this is what the middle of London really comprises, we realised that the network would become impossibly large and complicated. This gave us the very important hint that the amount of traffic to be planned for in our study area was likely to be controlled not by what might be needed within the area itself, but by what could be practically contrived in the way of a network to bring traffic to and from the area.”

And contrive they did. On their mental map they cleared away the entire neighbourhood, and replaced it with a hexagonal grid built for maximum traffic flow.

The humans and the buildings they used were relocated to a deck 20 ft in the air, only descending to ground to catch a bus on the arterial routes or unload a delivery van in a designated bay. Two levels beneath the ground were given over to parking, to provide an estimated 60,000 spaces. And it still wasn’t enough.

And this is why trains matter to abundance. To build the biggest cities, you cannot rely on the car - because it’s simply not up to the task. And to build without the car you have to learn to love the railway, with all its demands and foibles.

The right track

For all its drawbacks, the railway can handle enormous volumes of people, and usually has the advantage of a legacy network that is already woven into the city fabric. A project like London’s Crossrail, hooking up two pre-existing railway lines beneath the city to create a 32 trains-per-hour rail superhighway, is the sort of intervention on which the megacities of the future can be built. The places that this generates – bold skyscrapers and walkable suburbs – is an attractive vision of what the future can be.

And if you believe this is worth making happen, it’s important to realise that these things are difficult – they require a huge amount of coordination and patience. As JFK said of the moon landings, we do these things not because they are easy, but because they are hard. The challenge builds the soul. And if you are thinking for the long-term, you want to have these tools ready to be used ahead of when cities need them, and not be patching them together when the pressures are getting unbearable.

In his original tweet, Eli suggested that the same functionality in the future should be provided by new technologies like autonomous buses. I suspect he’s right, and in my government days, I tried to create something called Project LAVA – London Autonomous Vehicle Access – to do just that. But hindsight is the one thing you never can get on credit, and until people like me prove we’re right, everyone is entitled to believe in what already works.

The open goal

So yes – absolutely abundance has a place for trains. A good place – whether it’s building new suburbs and walkable communities; stacking up hives of urban creativity; or threading those centres together so their brilliance can harmonise.6 Without that urban vision, abundance is missing one of its defining features.

But equally abundance can and should be offering more. Transport quietly owns so much of our lives: Americans spend 93 billion hours a year driving; motorists worldwide spend thousands on petrol when they could be charging on electricity at a fraction of the cost. Clever infrastructure can give people the choice of new ways to travel in comfort – whether that is an e-bike on a spring morning or an autonomous pod back from a country pub. Planes that view the sound barrier as more of a guideline can make the world feel half the size.

All of this is there for abundance to claim. Transport used to be a one of the great proofs of progress; and the fact it has recently stalled is exactly the kind of aberration that abundance-minded people want to fix. Orville Wright lived to see the sound barrier broken; so a child today should expect to talk of supersonic passenger flight in something other than the past tense. Faster, higher, further, greener and in greater pleasure are all aims that transport is fit to prove.

So yes – an abundance of trains; but not at an expense of an abundance of everything else.

I assume my audience already knows its abundance from its elbow, but just in case - abundance is an idea that society should be enriched by making more of things, especially things (housing, clean energy, infrastructure and science) that in practice are held back by regulatory action or government disfunction. This year, Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s book Abundance has set out what this means for left-of-centre America, but the movement is notable for being politically broad

The rise of the motor car in particular drove the rise of concerns about the urban environment. Here is British transport thinking Colin Buchanan explaining to an early 1960s audience what the word ‘environment’ means.

For example, Beatrice and Sidney Webb, founders of the Fabian movement

Strangely, in 1910 there was no expectation that the masses would own motor cars, while in 2025 it is a certainty - one of the rare cases where politics has run in the opposite direction to ownership.

The first railways took off because they solved the challenge of how to turn the limited power of an early steam engine into a useful amount of motion. Steam carriages predated steam railways by decades, but were unworkable; the miracle came when inventors realised they could run the engine on the ‘railways’ used to allow horses to haul heavy loads at mines. That cut the rolling resistance and made powered land transport viable for the first time

It is not coincidence that the ten busiest air routes in the world are mostly short hops where train routes cannot/do not exist.