The next train to arrive will be...

Is the government about to announce HS2?

I think government has just tried to sneak a little secret out, ahead of next week’s 10 Year Infrastructure Strategy. Well, maybe not such a little one. While I’m not yet 100% sure, a little quirk in Wednesday’s spending review makes me think that before the month is out, government is going to announce that it will build HS2 to Manchester.

I’m conscious that this will make a lot of train people very excited, so I’d really better back that up with some evidence.

SHAMELESS PLUG - this week also saw me publish a big paper on speeding up planning. If you can’t understand why Britain seems to find it impossible to build these days, do have a read.

Background - a choice is unavoidable

You might remember HS2 to Manchester got cancelled in 2023. That’s true, but only up to a point.

For example, it might surprise you that, despite pulling the plug on the section of HS2 that ran from Crewe to Manchester, Rishi Sunak’s government was pushing forward with the High Speed Rail (Crewe to Manchester) Bill, that gives government the legal powers to actually build the railway. That’s not even an accident, for reasons we’ll come on to.

And then there’s the land. £429m worth of it, according to the NAO. Under the Crichel Down rules, government is obliged to sell land back that it has compulsorily purchased and no longer needs – but that sale couldn’t begin before the 2024 election was called, and the new Labour government pressed pause, while it sorted out its infrastructure strategy.

Excuses run out this week, when the 10 year infrastructure strategy lands. And at that point, government has to decide two things:

Whether or not to sell back the land

What legislation to proceed with (which requires deciding what line you are going to build)

Normally, the way governments handle difficult decisions is that you kick the can down the road. But this is a can that cannot be kicked.

Burnham’s scheme

All that was known back in July last year. The next piece of the puzzle came in mid-May, with the announcement of the Liverpool-Manchester Railway.

This was announced as a fantastic new railway line, working to connect central Liverpool and central Manchester, via the two airports. And, in the run-up to the Spending Review, one of the early announcements was that this project was going to be backed by government.

But this map carries a few secrets. Pay very close attention to two features

· The semi-transparent brown line marked ‘Proposed Cheshire connector’

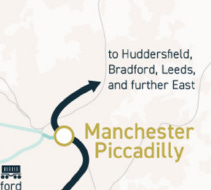

· The big arrow north of Manchester Piccadilly station

You may occasionally hear about different plans for upgrading the railway network around Manchester. There was HS2 phase 2B (western leg); Northern Powerhouse Rail; the Midlands-North West Rail Link and now this Liverpool Manchester Railway. If that seems a bit confusing, I have good news for you – they’re all the same thing.

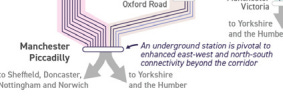

This isn’t an accident. Northern Powerhouse Rail (sometimes called HS3) was proposed to link Liverpool to Hull with a decent rail connection. When the route got near Manchester, the decision for the designers was between building a massive, expensive new through-running route underneath Manchester, or use the one HS2 was already building – which isn’t a hard decision to make. So NPR would run on the HS2 track from Milllington Junction to the new station at Manchester Piccadilly.

When HS2 was cancelled in 2023, NPR explicitly wasn’t. Which is why the Tories still needed that HS2 Crewe to Manchester bill – because it was necessary to build the Liverpool-Manchester route instead.1 And both the Birmingham-Liverpool and the Liverpool-Manchester plans similarly reuse the existing HS2 route alignments.

This isn’t a secret – it is consciously identified as a merit of the proposal to reuse existing statutory powers and route designs. The alternative would be years of expensive redesigns.

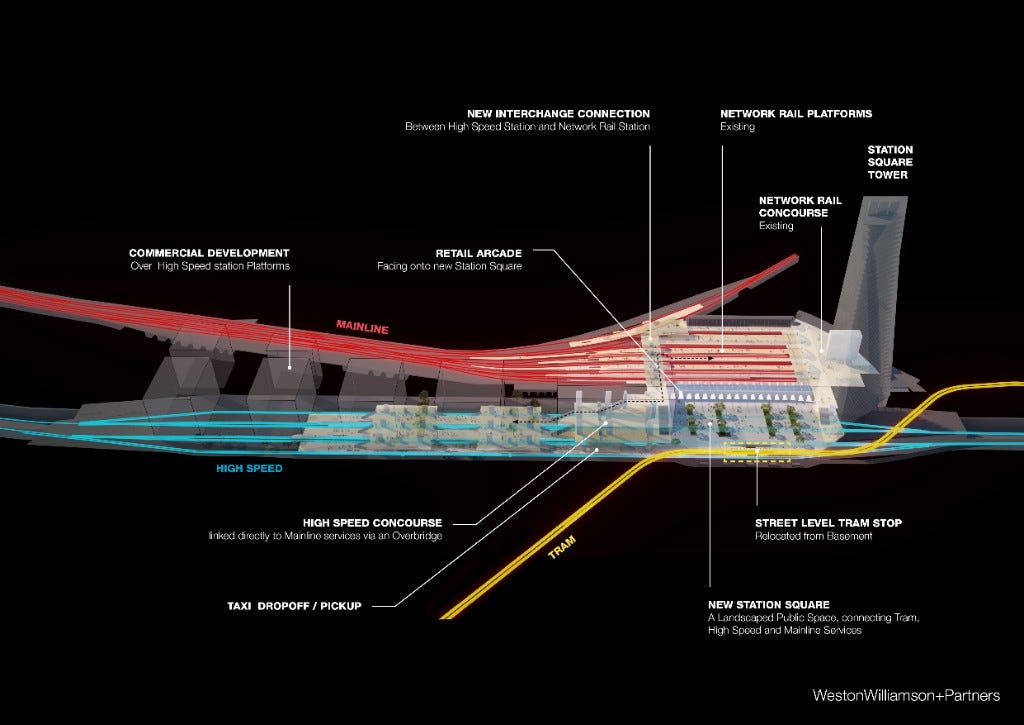

But there is one variation between the L-M railway and HS2 plans – shown by that big arrow – and it’s a doozy. As I’ve mentioned previously, the central debate for getting HS2 to Manchester was around the hugely-expensive proposed rebuild of Piccadilly Station. The choice was between an extremely expensive station that is a dead-end, or an astronomically expensive station that lets trains run through.2

And, now that Manchester is calling the shots, they are adamant that this project will have the through-running station.

What that means is that government has now backed almost all the hard bits of the western part of HS2 - the huge station rebuild plus a big tunnel to get it underneath the built area of Manchester itself. It’s also backing every single HS2 station, in one programme or another.

This by itself creates both a need and a logic for more HS2. A need, because there is very little chance indeed of justifying all that station building with a shuttle service from Liverpool to Manchester. A logic, because you’ve already done the most, second-most, third, fourth and fifth-hardest parts of HS2 by this point, and what’s left to finish the network is mostly construction over relatively open countryside. It may be so simple in comparison that it will even have a workable business case.

And, in case you forget, the Rail Minister is Lord Peter Hendy, who has spent a lifetime in rail and understands this all too well.

The guard that cannot lie

But a Liverpool-Manchester railway was going ahead under the last government. How do we get from here to my sense of certainty? This is where the Spending Review comes in. Not the media circus on Wednesday that the news likes to report on, but the real Spending Review – the published document that gives a precise account of the government’s forward spending plans.

This is normally a very techy document, of interest only to policy officials looking to see who won and lost in the great spending battle. But this year, it is a very useful document indeed. That’s because this document categorically must not lie. But it also has to avoid telling people what is in the 10 Year Infrastructure Strategy, which comes out in the next few days. So all of a sudden, the gaps and the silences become really important.

So, for example, it says nothing about road projects. And the road investment strategy is very likely to come out next week. So you might want to read up an old thread of mine to see what might fill that silence.

And on HS2, there have been some really careful words deployed. My eye was drawn to this:

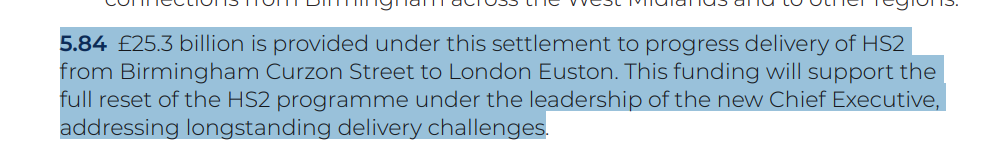

Now remember – it is absolutely essential that this document does not lie; and that if it says £Xbn is allocated to a thing, neither more nor less will be allocated to it. So the fact that the money is allocated very explicitly to HS2 from Curzon Street to Euston implies only two possible meanings. 1) HS2 has been permanently cancelled beyond Curzon Street, and no money will be spent elsewhere; or 2) they’ve very consciously making space for a second funding pot to do other bits of HS2.

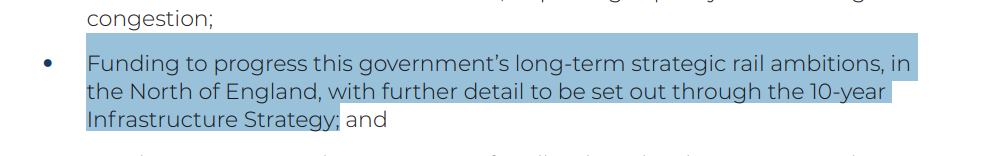

And just above that paragraph we find a promise of:

That’s big enough to park any rail project anywhere in the north beneath. It doesn’t have to be HS2, except that we also know the 10-year infrastructure strategy is where government has said it will make its HS2 decisions. Elsewhere in the document, the ten-year infrastructure strategy is explicitly promised to arrive before the end of the month.

So to recap

Government is obliged to take a stance on the remains of HS2

Government paused the land sales on the Manchester route

Government has just endorsed the most complicated unbuilt piece of HS2, where the business case won’t work without a connection to the south.

Government seems to have left a big HS2-sized patch of fog in its spending plans, exactly where next week’s infrastructure announcement will materialise.

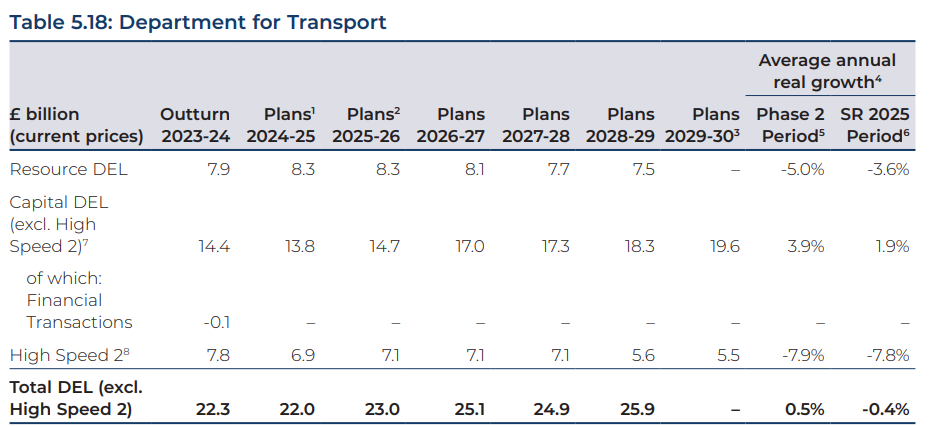

Oh, and there’s a £2.3bn/yr jump in DfT’s non-HS2 capital spending from next financial year. That could be lots of things, but I can tell you that there’s a lot of things it can’t be from the list of recent announcements, because they’re too far from construction.3

To me, this all points strongly, if circumstantially, towards there being an announcement about linking HS2 to Manchester next week.

The bad news

OK – that’s the good news (assuming you like HS2 - and if you read this far, odds are you do). But before you start dreaming of riding your HS2 train to Manchester, several words of caution.

First, HS2 Ltd is going through a massive reset, to understand just how badly messed up the project is. There are still a lot more skeletons to come out, and new CEO Mark Wild is rightly trying to get the whole project back under control. To be honest, this is about the worst possible moment to increase the project scope – which is why on balance I don’t think that mysterious extra money being allocated is to start construction of Phase 2A.4

Second, more high speed railway isn’t free. And government has no money. Right now, everything that can be handed over to private finance will be. The most likely funding source for more railway is some kind of private deal, and this takes time to arrange.

Third, there will be a real pressure to keep the costs down. The Midlands-North West Rail Link, worked up by the mayors post-cancellation of the leg to Manchester, did everything it could to cut costs. Some of those compromises have very significant consequences, which may end up looking penny-wise and pound-foolish.5 And there’s that station in Manchester – despite the assertions of Burnham & co, I doubt very much that Treasury considers itself signed up to a £12bn station.

I’d suspect that any announcement is more likely to be a promise to build a railway (maybe called HS2, maybe not) to Manchester at some point in the future. Close enough to justify big dreams in Manchester; but far enough away that it doesn’t show up as a big weight on the spending plan. And probably with enough time to really kick the tyres on the project.

Climbing out of the hole

And, compared to where we’re at today, that’s a win.

Sometimes, boosters for HS2 say ‘we can’t afford not to build it’. I have a gloomier version of the same thought: it may be hard to build HS2, but it’s harder not to build it. Or, putting it another way, I don’t think we have the capacity to move on from what we started.

Whatever the case for HS2, the case for Manchester is strong; and Manchester will be stuck if it’s always waiting for a railway that never materialises. And rail experts will tell you that, whatever the case for a Manchester-to-London railway, the West Coast Mainline is the busiest mixed-traffic railway in Europe and needs a bypass. It just happens that the simplest6 answer to all these questions is the same – build HS2. We will see every one of these individual problems through the same busted kaleidoscope, unless we finish the job.

And that’s what a good 10-year infrastructure plan should do. When I was lucky enough to lead the introduction of five-year planning to highways, I told my team there were no problems we could kick down the road – we now had to understand the answers to everything, even if we then chose to do nothing. Finishing HS2 (or decisively replacing it with a different plan) is what the 10-year plan needs to do in order to be worth the effort of writing it.

So here’s hoping that next week we can start climbing out the HS2 ditch – on the opposite side to the one we jumped in on.

The plan was to cut the Crewe-Millington section of the route from the bill via amendment - a plan that ceased to work the second the early election was called.

The expense of the station is hotly contested by Manchester authorities, who (not unreasonably) think that if DfT and HS2 can’t design a station for less than £12bn - six times the cost of the world’s most expensive train station - they should perhaps let someone else have a go.

Roads funding, which would include the Lower Thames Crossing, is explicitly set out and appears to be at current levels. East West Rail and TRU aren’t expecting those kinds of year-on-year spend increases, to the best of my knowledge.

Originally, the plan was to build Phase 2A alongside Phase 1, meaning the railway would bypass all of the worst bits of the West Coast Mainline in one go

In particular, decisions on reducing the line’s gauge clearance have huge knock-on consequences for the future of the UK rail fleet

I didn’t say cheapest. Or best.