What really ate Ebbsfleet?

And do spiders have jetpacks?

Back in January, I posted a story about the new town of Ebbsfleet in Kent, and how plans for a 15,000 home community were undone when Natural England turned the proposed town centre into a site of special scientific interest. One thing you’re never sure about when writing these threads is who, if anyone, will read them. So it was a bit of a surprise when, six weeks later, the PM used it as his example of the kind of behaviour government would sweep away to get building. And then, a few days later, environmental charities piled in to say that the story wasn’t true, and that the spiders weren’t blocking the town.

It's safe to say I wasn’t expecting this when I hit ‘post’. It’s also safe to say that if I’d known what would follow, I’d have done more footnotes.1 It didn’t leave me feeling good that people who presumably knew more than me about the site2 were saying I was wrong, and the end result was the PM and his planning reforms taking flak.

But … the one thing that was absolutely certain was that the site had been designated. And this had sunk the Ebbsfleet Central development. So, if this wasn’t because of the spiders, what had caused such a strange result?

I began digging. And found that Natural England had taught these spiders a truly amazing trick…

Had I got it wrong?

I should quickly recap what the argument is about. In the 2000s we built a high speed railway line to link the Channel Tunnel to London. Along the way, the line runs through some post-industrial wasteland, and clever people decided to build a station and create a new town, called Ebbsfleet, on the brownfield site.

Ebbsfleet always seemed a bit cursed and struggled to build anything. But by 2021 it looked like it had turned a corner – it had bought £35m of land and set out a plan for a massive urban layout. It was all going so well, until the development corporation3 suddenly received a letter from Natural England announcing that they intended to designate the site of the town centre, together with most of the land around the railway station, as a site of special scientific interest (SSSI). That means that building on it became near-impossible. And, despite some spiky objections from the development corporation, Natural England pushed ahead and designated the site.

The result of which was that, while bits of Ebbsfleet are being built, they don’t include the town centre or anything other than car parks to fill the half-mile gap between the houses and the train station with an 18 minute journey to central London.

The proposed construction site could not be mistaken for pristine nature. A large chunk was ex-landfill, mixed with exhausted quarries. Natural England’s own words for it were “high pH and significant concentrations of chloride, sulphate and potassium associated with [cement kiln] dust result in greatly stunted plant growth”. It sounds like a textbook definition of the ‘grey belt’ that the government now wants to turn into houses.

But the very fact of its polluted, blasted nature meant that it provided a perfect habitat for certain types of species, particularly invertebrates. One affected species – the distinguished jumping spider – is a bit of a superstar species from a conservation point of view, limited to two sites in England and classed as critically endangered.

My interpretation from Natural England’s decision documents was that the spiders and another endangered species, the five-banded weevil wasp, were the strongest reason for designation of the station land.4 And you’d need to have a strong reason, because there seemed to be little else of high environmental value5 around the station itself.

Had I, like a distinguished spider, jumped to the wrong conclusion? Well, sort of…

The case of the missing spiders

My digging began by asking Natural England for the material that had justified the designation of the site. Eventually, they sent me 1500 pages of environmental surveys. No one could accuse them of holding anything back.

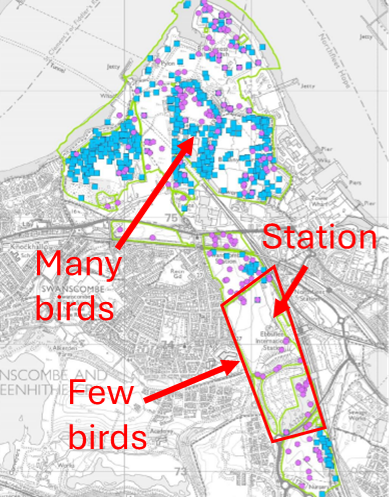

That included all the detailed information about every wildlife survey they had – three big ones in 2012, 2015 and 2020 – and it included the location of every species and specimen they had found.6 And it was absolutely true that they had not found any distinguished jumping spiders anywhere near the station. Indeed, they’d hardly found any distinguished jumping spiders at all – the only sightings were in the 2012 survey, when two had been found at an electricity pylon and a jetty over a mile from the affected land.7

That seems decisive, doesn’t it? Just as the charities said, the distinguished jumping spider wasn’t in the way of Ebbsfleet. Indeed, it’s not guaranteed the distinguished jumping spider is still there.8

Sounds like I was wrong. But before I apologised to anyone, I needed to understand – why was the site designated?

The real nature value

I decided I needed more help, and I connected with a very helpful man at Buglife9 – the national charity for invertebrates. I explained the conundrum I was working through, and he took me through the background.

Ahead of 2021, Buglife had been one of several environmental charities lobbying for the designation of the Swanscombe peninsula (which is the formal name of the Ebbsfleet site) as a SSSI. That process was heated given that for most of that time there was a plan to build a theme park on the peninsula, which would have unavoidably hit the nature value. He also pointed out that Natural England had a list of 20-ish priority locations for environmental designation, and ‘Thames Estuary Invertebrates’ had long been on the list – so designation shouldn’t have been a bolt from the blue.

The argument for this was that there was a huge variety of threatened species on the site – 250 different species of concern – making it the richest biodiversity site on the Thames Estuary. And one of those species (you’ll have guessed which) had an endangered status that they argued should put it on a fast lane to environmental designation on its own.10

But there was a quirk. The land he was talking about – this rich biodiversity oasis – was not the land I was talking about.

Passing the land parcel

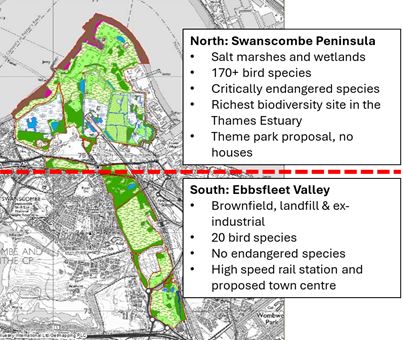

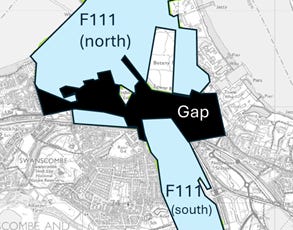

The first clue to the puzzle is that the SSSI at Ebbsfleet is actually two distinct areas.

The north is the bit where the theme park was proposed, and where nature charities have been fighting hard for designation. And, FWIW, I’d agree with the charities that there is a good case for that.

But the south – that’s another story. No one was arguing for designating this. I asked my invertebrate expert, and he was clear that the invertebrates he was protecting (including the jumping spider) were up in the north of the site. He hadn’t given much thought to the southern end, but wondered if it might had been something to do with birds, or plants.

He connected me with another helpful person at the RSPB. Who said, without wanting to speak against the biodiversity value of the south, said the northern end had Marsh Harriers and Bearded Reedlings; Grasshopper Warblers and Nightingales, all with valuable breeding pairs – and that had all their attention. I did my own checking of the survey data, and of the 210 species bird species recorded in the area, 171 were in the marshes and 20 were at the landfill.11 The scarcest birds near the station were skylarks,12 of which the UK has about 1.4 million.13

And it won’t be the plants, because they have to cut down everything on the landfill every July to stop the site catching fire.14

So there were no distinguished jumping spiders,15 no other really rare species and no one was asking to protect the land. And it now appeared that the PM and the environment charities were effectively arguing about two different sites. What on earth was going on?

WTF111?

It seemed impenetrable. Natural England had taken in the evidence calling for protection of the north; and a few months later the black box of its reasoning had spat out a decision protecting the south as well. Try as I might, I could not work out which animal or plant they were trying to protect.

And then I had the eureka moment. They weren’t protecting the creatures. They were protecting the land.

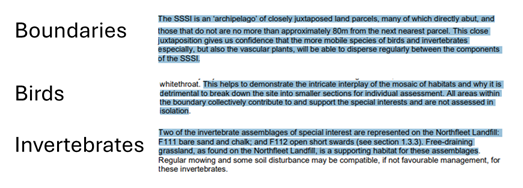

Since the 1980s there has been more expansive thinking about how to protect a protected species. Environmentalists rightly point out that a species is part of an ecosystem, and it can need more land than just its immediate habitat. So their focus has shifted from protecting the creatures to protecting their context as well – areas of land called ‘assemblages’16 and ‘mosaics’.

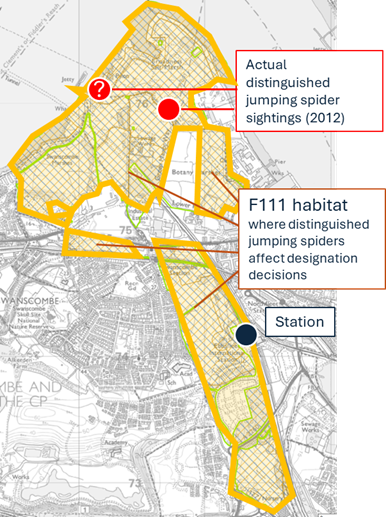

Different types of land are coded systematically in environmental surveys. So, for example, the land which the distinguished jumping spider likes is labelled F111. Land across the survey area is assessed the same way. And provided land of one type is joined up or reasonably close, it fuses together to become a single assemblage.

And assemblages are protected as one. So if you try to point out that a particular area does not contain any of the species being protected, Natural England will reply that this may be true, but the wider assemblage does contain it; and the assemblage will assessed as a single unit. So when the owners of the land directly outside of the station objected to its inclusion, on the basis there was no nature there, they were told that it basically didn’t matter. If the land contained F111 or F112, or adjoined a similar area with birdlife, or was part of a pathway from one part of the site to another – then it was fair game.

So it’s true no distinguished jumping spiders were found near the station. But there is F111 land next to the station. And under the Natural England methodology, all F111 land in the assemblage is treated as a single, homogenous unit. So the spiders, and all the other species across the F111, are treated as ‘being’ everywhere within the assemblage when designating a site, even though in this case they were more than a mile away.

This may sound a bit far-fetched, so here’s Natural England confirming it to me in an FOI.

To put that in map terms, it looks like this – with the red dots being where the critically endangered spiders were seen, and orange area being the land where the case for designation is materially affected as a result of their presence.

Now, I should be explicit: there are more species in play here than just the jumping spiders, some which do live much closer to the station. 17These other species are not formally endangered, but some are still rated as nationally scarce. But the fact remains that biodiversity value is effectively being teleported across the map.

This also, at last, gives us our explanation of why the southern site was designated as well. There was no particular species that needed preserving. But the logic was that once a key species was found, Natural England guidance18 says a site should contain whole ecological units – so once you have some F111 (or F112, or M311 or lowland grass scrub) filled with a protected species, you keep going until it runs out. And in this case, the F111 didn’t stop where the charities’ requests had ended – it kept going and going, covering over the Ebbsfleet masterplan like a knocked-over can of paint, finally coming to a halt at eight-lanes of the A2.

And now for one final twist…

The punchline

There is one important rule that you have to follow with these assemblages – the different parts do actually have to be physically near one another. Not necessarily touching – but close enough that the relevant species can get from one to the other. And at Ebbsfleet, we have a bit of a problem. Because the site doesn’t join up.

Look at this map and you’ll see the problem. Between the north and the south parts of the site, we have a gap two roads, a railway line and a very unappealing industrial estate filled with scrapyards, waste management companies, parked lorries and so on. A small gap isn’t unreasonable; but this isn’t small.

The Natural England documentation sounded a bit defensive on this point, and Ebbsfleet development corporation had clearly brought the question up in discussions. According to the author of the designation report:

“The close proximity of the various component parts of the site, with most directly abutting others and those that do not no more than c.80m from the next component, coupled with the known mobility of elements of the special interest, means that the site is indivisible in terms of its special interest. A site that encompasses the full extent of its special interest is more resilient than one that does not.”

80m is a bit of a fib. There is technically a route from north to south that has no gap greater than 80m, but it involves two 80m gaps, with several trips down narrow 10m strips of land out the back of places with names like Frank’s Steel or Alfa Tail Lifts. The gap is typically more like 300m, or 250m if our invertebrates don’t mind crossing HS1.

But there’s also one other thing. You have to cross the A226.

The A226 is not a wide road. On a map it does not look particularly special. But the problem becomes apparent if you take a look in 3D…

That’s not just a road. It’s a 25m high wall of chalk. The road runs through old quarries, which were dug down and down on both sides to make cement for London, resulting in something four times the height of the Great Wall of China. If you want to understand the scale, look for yourself on Google Maps; or just look at the diggers, which could be mistaken for children’s toys.

So yes – if creatures cross the high speed rail line and the industrial estate, travel a quarter of a kilometre, scale a 25m cliff, cross a road and then descend another cliff, they can get to the other half of the site. But unless the jumping spiders have upgraded to jetpacks, you’d think it was fairly clear this cuts the site in half.

It would be quite significant if it did. Because that would mean the assemblages in the north of the site didn’t extend into the southern area. It would mean the southern area wouldn’t form part of the northern site, and would need to apply for designation on their own, which would take many years and wouldn’t benefit from the support of that that long-term Natural England priority list when it did so. And it couldn’t cite the most threatened species either, meaning designation would be less likely to be approved.

All of that would have meant that Ebbsfleet Central would have been built, £25m of public money preserved, and the Prime Minister left to worry about other things. But, as we know, it didn’t work out that way. Somehow, despite being 25m tall, this barrier got overlooked.

Where this leaves us

Everyone in these stories says that they want to see a balance of nature and other priorities. In this case, there very nearly was that balance. There’s a parallel universe where Natural England just did what the nature charities suggested in January 2021, and where today the first residents of Ebbsfleet Central are walking around the peninsula,19 saying how nice it is that all this nature has been preserved.

But we didn’t go there. The reasons for that are all inside of a black box in Natural England. A policy primed to protect nature in every way that it can, even if that means gutting a new town or blocking off use of hundreds of hectares because they are adjacent to something precious. An ability at the same time to overlook potential obstacles like 25m cliffs. Stating the obvious, if we want a balanced system for protecting nature, we want something that doesn’t work like this.

We’re about to have a big fight over biodiversity, as government plans a second bill on planning reform. And you can see two sides digging their trenches and preparing to stop listening. Some people will probably relish the fight.

But most of us want to have good, responsible nature protections. And if we don’t have that right now, we ought to want the reforms that deliver them. Things like giving Natural England a statutory requirement to pursue sustainable development, and ending the nonsense of them declining to discharge their growth duty like the rest of government.20 And maybe having a quiet word about writing policy documents that are a little less uncompromising.21

And it isn’t too late to save Ebbsfleet. Angela Rayner has the power to approve developments anywhere, even in the middle of a SSSI. That would be an extreme step, and definitely not something you do based on someone’s substack alone. But we’ve had quite a few extreme steps to get us to this point, and we could survive one going back towards where we began.

So this time, so many footnotes!!!

We’ll come back to this...

A development corporation is not, as the name might imply, a private building company - it is a public body reporting to the Secretary of State for Housing and Local Government. This is all a tussle between two different bits of government

Plus, for completeness, a small patch of protected vetch; and a pre-existing geological feature called Baker’s Hole, which already had a SSSI of its own

Full disclosure - the 2020 survey results sent to me didn’t include the last two site surveys. If anyone has those, and they contradict my analysis, I defer to them.

LRCH 2012 Terrestrial invertebrates survey section 3.3; The London Resort Appendix 12.1: Ecology Baseline Report paras 3.94-3.95

Surveying tiny spiders is genuinely hard, so let’s assume that they didn’t die out.

I would thank them by name, but the last time I posted on this I got some bad trolls, and I don’t think they’ll thank anyone who helped me

Wintering birds report 2016, para 3.1.8. Breeding birds report 2016 describes the site of ‘neighbourhood significance’ - the lowest level possible

As you can see from the map below, there are areas of greater birdlife further south, near the junction with the A2.

I didn’t reach out to the plants people, but it was pretty clear from the surveys that the feature of most interest is the wildflower meadows filled with rare orchids which are (you guessed it) on the theme park site.

LPER Invertebrate Survey Report para 2.17

Technically, there is actually another type of jumping spider found at the station, just not an endangered one.

e.g. Chapter 20 Terrestrial and Freshwater Invertebrates section 3.10

Though, to be equally explicit, they also live in the northern part of the site as well.

Once they’d got over the cliff and the industrial estate, of course

Natural England says that the growth duty in the Deregulation Act 2015 does not apply to them, as they are not a regulator. This would be a stronger argument if that was something actually written in the law parliament passed, rather than their own in-house interpretation of it.

For example, this section from their guidance on defining the boundaries of a SSSI

https://data.jncc.gov.uk/data/dc6466a6-1c27-46a0-96c5-b9022774f292/SSSI-Guidelines-Part1-Rationale-2013.pdf

“The loss or damage to any part of a site cannot be justified by the survival of the larger fraction of the site, since, once the process of fragmentation has begun, there are no logical stopping points short of total loss of the site. We will not set arbitrary limits of acceptable loss as this would fundamentally undermine the consistency of approach which is the credible basis for SSSI selection. Small incursions into protected sites are often disproportionately large in their direct ecological effects. The concept of site integrity may seem far-fetched when the defining boundaries are artificial, but any further intrusions make an already unsatisfactory situation worse.”

Unsure if this is primarily comedy or tragedy, thanks either way

Perhaps there could be a narrower connection along the the Ebbsfleet River to connect the southern site to the countryside to the south? Would need a crossing of the A2 also.